Pushing our Container to AWS ECR

In the first part of this blog series we saw how to create a local docker image containing a simple web server program. In order to run this server remotely, we have to upload this image somewhere to deploy it.

One service that lets us deploy docker images is Amazon Web Services (AWS). In this article, we're going to take the first step, and walk through the process of publishing our container image to the AWS Elastic Container Registry (ECR). Next time around, we'll see how to actually deploy our application using this image.

In principle, publishing the image is a simple task. But in my experience with AWS, the processes and documentation just aren't quite as clear as one would like them to be. There tend to be a lot of branches in their tutorials, and it's often not clear which path is the right path. The sheer amount of AWS-specific terminology can get extremely confusing, and this can make it hard to know if you've satisfied the prerequisites for the tutorial.

So in this article I'm going to be as explicit as possible, and include a video at the end so you can follow along. Here's the high level overview:

- Create an AWS account

- Create an ECR Repository

- Install the AWS Command Line Interface

- Login using the CLI

- Push the container using Docker

Create an AWS Account

First of course, you need to create an account with Amazon Web Services. This is a separate account from a normal Amazon account. But a massive gotcha is that you should not use the exact email address from your Amazon account. This can cause a weird loop preventing you from logging in successfully (see this Stack Overflow issue).

If you have Gmail though, it should work to use the '+' trick with email aliases. So you can have `name@gmail.comfor your Amazon account andname+aws@gmail.com` for your AWS account.

Create an ECR Repository

Next you'll need to login to your account on the web portal and create an ECR repository. To do this, you'll simply click the services tab and search for "Elastic Container Registry". Assuming you have no existing repositories, you'll be prompted with a description page of the service, and you'll want to find the "Get Started" button under the "Create a Repository" header off in the top right corner.

The only thing you need to do on the next page is to assign a name to the repository. The prefix of the repository will always have the format of {account-id}.dkr.ecr.{region}.amazonaws.com, where the account ID is a 12-digit number.

If you want, you can also set the repository as public, but my instructions will assume that you'd made a private repository. To finish up, you'll just click the "Create Repository" button at the bottom of the page. This part is also covered in the video at the bottom if you want to see it in action!

Install the AWS CLI

Our next few actions will happen on our local command line prompt. To interact with our AWS account, we'll need to install the AWS Command Line Interface. To install these tools, you can follow this user guide. It is fairly straightforward to follow once you select your operating system. You know it's succeeded when the command aws --version succeeds on your command line.

Login Using the CLI

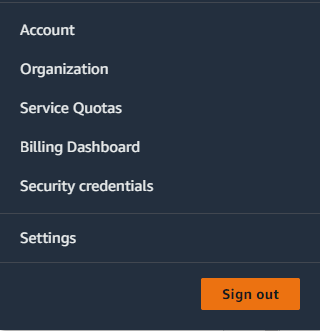

Now assuming you created a private repository, you'll need to authenticate on the command line. The first step in this process is to create an access key. You can do this from the web portal by clicking your account name in the top right corner to open up a menu and then going to the "Security Credentials" page. There's a section for "Access Keys" about midpage, and you'll want to use "Create Access Key".

If you do this as a "root" user, AWS will warn you that this is not the advised practice and you should instead create such keys as an "IAM User". But it is possible to do use root for demonstration purposes.

You'll want to copy the "Access Key ID" and the key itself. The latter must be copied or downloaded before you leave the page (you can't come back to it later).

You can then login using the aws configure command in your command line terminal. This will ask you to enter your access key ID and then the key itself, as well as the region.

Now that you're authenticated with AWS, we have to allow AWS to login to Docker for us. The following command would give us the Docker password for AWS in the us-west-2 region:

>> aws ecr get-login-password --region us-west-2We can pipe this password into the docker login command and connect to the repository we created with this command, where you should substitute your region and your account ID.

>> aws ecr get-login-password --region {region} | \

docker login --username AWS --password-stdin {account-id}.dkr.ecr.{region}.amazonaws.comNote how you actually do not need the repository name for this command! Just the prefix formed by your account and the region ID.

Pushing the Image

Now that we're authenticated, we just need to push the container image. We'll start by reminding ourselves of what our image ID is:

>> docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID ...

quiz-server latest b9eab6a22b12 ...The first thing we need to do is provide a "tag" for this image corresponding to the remote ECR repository we created. This requires the image ID and the full repository URI. We'll also attach :latest to indicate that this is the most recent push. Here's the specific command I used for my IDs:

>> docker tag b9eab6a22b12 165102442442.dkr.ecr.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/quiz-server:latestHere's a more generic command template:

>> docker tag {image-id} {account-id}.dkr.ecr.{region}.amazonaws.com/{repo-name}:latestFinally, we just need to push it using this new repository/tag combo! Here's what it looks like for me:

>> docker push 165102442442.dkr.ecr.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/quiz-server:latestAnd more generically:

>> docker push {account-id}.dkr.ecr.{region}.amazonaws.com/{repo-name}:latestYou should then be able to see your image if you head to your ECR dashboard!

Video Walkthrough

If you want to see all this in action, you can head to YouTube and take a look at the video walkthrough! If you are enjoying this series, make sure to subscribe to our monthly newsletter!

AoC 2022: The End!

I've completed the final two video walkthroughs of problems from Advent of Code 2022! You can view them on my YouTube Channel, or find links to all solutions on our summary page.

Day 24 is the final graph problem, one that involves a couple clever optimizations. See the video here, or you can read a written summary as well.

And last of all, Day 25 introduces us to the concept of balanced quinary. Quinary is a number system like binary or ternary, but in the balanced form, characters range for (-2) to 2 instead of 0 to 4. This final video is on YouTube here, or you can read the write-up.

I promise there will be more problem-solving related content later this year! If these videos and walkthroughs have helped you improve your skills, make sure to subscribe to our monthly newsletter so you stay up to date!

Creating a Local Docker Image

Running a web server locally is easy. Deploying it so other people can use your web application can be challenging. This is especially true with Haskell, since a lot of deployment platforms don't support Haskell natively (unlike say, Python or Javascript). In the past, I've used Heroku for deploying Haskell applications. In fact, in my Practical Haskell and Effectful Haskell courses I walk through how to launch a basic Haskell application on Heroku.

Unfortunately, Heroku recently took away its free tier, so I've been looking for other platforms that could potentially fill this gap for small projects. The starting point for a lot of alternatives though, is to use Docker containers. Generally speaking, Docker makes it easy to package your code into a container image that you can deploy in many different places.

So today, we're going to explore the basics of packing a simple Haskell application into such a container. As a note, this is different from building our project with stack using Docker. That's a subject for a different time. My next few articles will focus on eventually publishing and deploying our work.

Starting the Dockerfile

So for this article, we're going to assume we've already got a basic web server application that builds and runs locally on port 8080. The key step in enabling us to package this application for deployment with Docker is a Dockerfile.

The Dockerfile specifies how to set up the environment in which our code will operate. It can include instructions for downloading any dependencies (e.g. Stack or GHC), building our code from source, and running the necessary executable. Dockerfiles have a procedural format, where most of the functions have analogues to commands we would run on a terminal.

Doing all the setup work from scratch would be a little exhausting and error-prone. So the first step is often that we want to "inherit" from a container that someone else has published using the FROM command. In our case, we want to base our container off of one of the containers in the Official Haskell repository. We'll use one for GHC 9.2.5. So here is the first line we'll put in our Dockerfile:

FROM haskell:9.2.5Building the Code

Now we have to actually copy our code into the container and build it. We use the COPY command to copy everything from our project root (.) into the absolute path /app of the Docker container. Then we set this /app directory as our working directory with the WORKDIR command.

FROM haskell:9.2.5

COPY . /app

WORKDIR /appNow we'll build our code. To run setup commands, we simply use the RUN descriptor followed by the command we want. We'll use 2-3 commands to build our Haskell code. First we use stack setup to download GHC onto the container, and then we build the dependencies for our code. Finally, we use the normal stack build command to build the source code for the application.

FROM haskell:9.2.5

...

RUN stack setup && stack build --only-dependencies

RUN stack buildRunning the Application

We're almost done with the Dockerfile! We just need a couple more commands. First, since we are running a web server, we want to expose the port the server runs on. We do this with the EXPOSE command.

FROM haskell:9.2.5

...

EXPOSE 8080Finally, we want to specify the command to run the server itself. Supposing our project's cabal file specifies the executable quiz-server, our normal command would be stack exec quiz-server. You might expect we would accomplish this with RUN stack exec quiz-server. However, we actually want to use CMD instead of RUN:

FROM haskell:9.2.5

...

CMD stack exec quiz-serverIf we were to use RUN, then the command would be run while building the docker container. Since the command is a web server that listens indefinitely, this means the build step will never complete, and we'll never get our image! However, by using CMD, this command will happen when we run the container, not when we build the container.

Here's our final Dockerfile (which we have to save as "Dockerfile" in our project root directory):

FROM haskell:9.2.5

COPY . /app

WORKDIR /app

RUN stack setup && stack build --only-dependencies

RUN stack build

EXPOSE 8080

CMD stack exec quiz-serverCreating the Image

Once we have finished our Dockerfile, we still need to build it to create the image we can deploy elsewhere. To do this, you need to make sure you have Docker installed on your local system. Then you can use the docker build command to create a local image.

>> docker build -t quiz-server .You can then see the image you created with the docker images command!

>> docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID ...

quiz-server latest abcdef123456 ...If you want, you can then run your application locally with the docker run command! The key thing with a web server is that you have to use the -p argument to make sure that the exposed ports on the docker container are then re-exposed on your local machine. It's possible to use a different port locally, but for our purposes, we'll just use 8080 for both like so:

>> docker run -it -p 8080:8080 --rm quiz-serverConclusion

This creates a local docker image for us. But this isn't enough to run the program anywhere on the web! Next time we'll upload this image to a service to deploy our application to the internet!

If you want to keep up with this series, make sure to subscribe to our monthly newsletter!

3 More Advent of Code Videos!

I'm almost done with the Advent of Code recap videos. This week you can now find the reviews for Days 21, 22, and 23 by going to my YouTube Channel. As a reminder, you can find links to all Advent of Code solutions on this page.

Day 21 featured a recursive variable tree problem. See the video here or read the write-up.

Day 22 started out as an innocuous 2D maze traversal problem, but ended up being waaay more complicated in part 2, which puts your geometry skills to the test and forces some very precise programming. Watch the recap or read about it.

Finally, Day 23 was the final state evolution problem. Our elf friends want to plant a grove of trees, so they would like to spread out in an optimal fashion. Here's the video, and here's the blog post.

If these recaps have helped you improve your Haskell problem solving skills, make sure the subscribe to our monthly newsletter! We'll have a lot more problem-solving content throughout the year, so stay tuned for that!

What's Next in 2023?

To start the year I wrote a few different articles about Chat GPT looking at what it thinks about Haskell. After some extra reflection, my emotional reaction probably matched that of a lot of other programmers. I felt plenty of excitement about the tasks that could become a lot easier using AI tools, but also a twinge of existential panic over the prospect of being replaced as a programmer. This latter feeling was especially acute when I thought about the future of this blog.

After all, what's the point of writing a blog post about a topic when someone can type their question into Chat GPT, get a response, and then even have a coherent conversation about the details?

However, there are still plenty of things that Chat GPT isn't able to help with yet. And as I'm planning out what I'm going to write about over the next year, I want to focus on material that isn't quite so replaceable.

The most pithy distinction that will be guiding me is show, don't tell. AI can tell you what you really want to know, but it's still going to be a long time before it can really show it to you in the context you want to use it. Even if you can have a coherent conversation with a chatbot, this doesn't mean it can adequately respond to all the needs you can present for a larger project. You can't just feed in your whole codebase to Chat GPT and have it tell you what you need to write next.

So on the blog this year, you can expect a lot of content will be more project-based. I'll be working on some larger, overarching ideas. I'll often be presenting these more through video than written style, since a video presents more of the context and struggles you can expect while actually creating something.

Another distinction with AI is that it can tell you what to learn, but not necessarily how to learn it. It doesn't necessarily know how humans acquire knowledge, especially in something as complex as programming. So you can expect more course-related content in this area, but I'll be aiming for multiple shorter courses (including one or two free courses) this year to complement the existing, longer course offerings.

If you want to keep up to date with all this, make sure to subscribe to our monthly newsletter!

Advent of Code: Fetching Puzzle Input using the API

When solving Advent of Code problems, my first step is always to access the full puzzle input and copy it into a file on my local system. This doesn't actually take very long, but it's still fun to see how we can automate it! In today's article, we'll write some simple Haskell code to make a network request to find this data.

We'll write a function that can take a particular year and day (like 2022 Day 5), and save the puzzle input for that day to a file that the rest of our code can use.

As a note, there's a complete Advent of Code API that allows you to do much more than access the puzzle input. You can submit your input, view leaderboards, and all kinds of other things. There's an existing Haskell library for all this, written in 2019. But we'll just be writing a small amount of code from scratch in this article, rather than using this library.

Authentication

In order to get the puzzle input for a certain day, you must be authenticated with Advent of Code. This typically means logging in with GitHub or another service. This saves a session cookie in your browser that is sent with every request you make to the site.

Our code needs to access this cookie somehow. It's theoretically possible to do this in an automated way by accessing your browser's data. For this example though, I found it easier to just copy the session token manually and save it as an environment variable. The token doesn't change as long as you don't log out, so you can keep reusing it.

This GitHub issue gives a good explanation with images for how to access this token using a browser like Google Chrome. At a high level, these are the steps:

- Log in to Advent of Code and access and puzzle input page (e.g. http://adventofcode.com/2022/day/1/input)

- Right click the page and click "inspect"

- Navigate to the "Network" tab

- Click on any request, and go to the "Headers" tab

- Search through the "Request Headers" for a header named

cookie. - You should find one value that starts with

session=, followed by a long string of hexadecimal characters. Copy the whole value, starting withsession=and including all the hex characters until you hit a semicolon. - Save this value as an environment variable on your system using the name

AOC_TOKEN.

The rest of the code will assume you have this session token (starting with the string session=) saved as the variable AOC_TOKEN in your environment. So for example, on my Windows Linux subsystem, I have a line like this in my .bashrc:

export AOC_TOKEN="session=12345abc..."We're now ready to start writing some code!

Caching

Now before we jump into any shenanigans with network code, let's first write a caching function. All this will do is see if a specified file already exists and has data. We don't want to send unnecessary network requests (the puzzle input never changes), so once we have our data locally, we can short circuit our process.

So this function will take our FilePath and just return a boolean value. We first ensure the file exists.

checkFileExistsWithData :: FilePath -> IO Bool

checkFileExistsWithData fp = do

exists <- doesFileExist fp

if not exists

then return False

...As long as the file exists, we'll also ensure that it isn't empty.

checkFileExistsWithData :: FilePath -> IO Bool

checkFileExistsWithData fp = do

exists <- doesFileExist fp

if not exists

then return False

else do

size <- getFileSize fp

return $ size > 0If there's any data there, we return True. Otherwise, we need to fetch the data from the API!

Setting Up the Function

Before we dive into the specifics of sending a network request, let's specify what our function will do. We'll take 3 inputs for this function:

- The problem year (e.g. 2022)

- The problem day (1-25)

- The file path to store the data

Here's what that type signature looks like:

fetchInputToFile :: (MonadLogger m, MonadThrow m, MonadIO m)

=> Int -- Year

-> Int -- Day

-> FilePath -- Destination File

-> m ()We'll need MonadIO for reading and writing to files, as well as reading environment variables. Using a MonadLogger allows us to tell the user some helpful information about whether the process worked, and MonadThrow is needed by our network library when parsing the route.

Now let's kick this function off with some setup tasks. We'll first run our caching check, and we'll also look for the session token as an environment variable.

fetchInputToFile :: (MonadLogger m, MonadThrow m, MonadIO m) => Int -> Int -> FilePath -> m ()

fetchInputToFile year day filepath = do

isCached <- liftIO $ checkFileExistsWithData filepath

token' <- liftIO $ lookupEnv "AOC_TOKEN"

case (isCached, token') of

(True, _) -> logDebugN "Input is cached!"

(False, Nothing) -> logErrorN "Not cached but didn't find session token!"

(False, Just token) -> ...If it's cached, we can just return immediately. The file should already contain our data. If it isn't cached and we don't have a token, we're still forced to "do nothing" but we'll log an error message for the user.

Now we can move on to the network specific tasks.

Making the Network Request

Now let's prepare to actually send our request. We'll do this using the Network.HTTP.Simple library. We'll use four of its functions to create, send, and parse our request.

parseRequest :: MonadThrow m => String -> m Request

addRequestHeader :: HeaderName -> ByteString -> Request -> Request

httpBS :: MonadIO m => Request -> m (Response ByteString)

getResponseBody :: Response a -> aHere's what these do:

parseRequestgenerates a base request using the given route string (e.g.http://www.adventofcode.com)addRequestHeaderadds a header to the request. We'll use this for our session token.httpBSsends the request and gives us a response containing aByteString.getResponseBodyjust pulls the main content out of theResponseobject.

When using this library for other tasks, you'd probably use httpJSON to translate the response to any object you can parse from JSON. However, the puzzle input pages are luckily just raw data we can write to a file, without having any HTML wrapping or anything like that.

So let's pick our fetchInput function back up where we left off, and start by creating our "base" request. We determine the proper "route" for the request using the year and the day. Then we use parseRequest to make this base request.

fetchInputToFile :: (MonadLogger m, MonadThrow m, MonadIO m) => Int -> Int -> FilePath -> m ()

fetchInputToFile year day filepath = do

isCached <- liftIO $ checkFileExistsWithData filepath

token' <- liftIO $ lookupEnv "AOC_TOKEN"

case (isCached, token') of

...

(False, Just token) -> do

let route = "https://adventofcode.com/" <> show year <> "/day/" <> show day <> "/input"

baseRequest <- parseRequest route

...Now we need to modify the request to incorporate the token we fetched from the environment. We add it using the addRequestHeader function with the cookie field. Note we have to pack our token into a ByteString.

import Data.ByteString.Char8 (pack)

fetchInputToFile :: (MonadLogger m, MonadThrow m, MonadIO m) => Int -> Int -> FilePath -> m ()

fetchInputToFile year day filepath = do

isCached <- liftIO $ checkFileExistsWithData filepath

token' <- liftIO $ lookupEnv "AOC_TOKEN"

case (isCached, token') of

...

(False, Just token) -> do

let route = "https://adventofcode.com/" <> show year <> "/day/" <> show day <> "/input"

baseRequest <- parseRequest route

{- Add Request Header -}

let finalRequest = addRequestHeader "cookie" (pack token) baseRequest

...Finally, we send the request with httpBS to get its response. We unwrap the response with getResponseBody, and then write that output to a file.

fetchInputToFile :: (MonadLogger m, MonadThrow m, MonadIO m) => Int -> Int -> FilePath -> m ()

fetchInputToFile year day filepath = do

isCached <- liftIO $ checkFileExistsWithData filepath

token' <- liftIO $ lookupEnv "AOC_TOKEN"

case (isCached, token') of

(True, _) -> logDebugN "Input is cached!"

(False, Nothing) -> logErrorN "Not cached but didn't find session token!"

(False, Just token) -> do

let route = "https://adventofcode.com/" <> show year <> "/day/" <> show day <> "/input"

baseRequest <- parseRequest route

let finalRequest = addRequestHeader "cookie" (pack token) baseRequest

{- Send request, retrieve body from response -}

response <- getResponseBody <$> httpBS finalRequest

{- Write body to the file -}

liftIO $ Data.ByteString.writeFile filepath responseAnd now we're done! We can bring this function up in a GHCI session and run it a couple times!

>> import Control.Monad.Logger

>> runStdoutLoggingT (fetchInputToFile 2022 1 "day_1_test.txt")This results in the puzzle input (for Day 1 of this past year) appearing in the `day_1_test.txt" file in our current directory! We can run the function again and we'll find that it is cached, so no network request is necessary:

>> runStdoutLoggingT (fetchInputToFile 2022 1 "day_1_test.txt")

[Debug] Retrieving input from cache!Now we've got a neat little function we can use each day to get the input!

Conclusion

To see all this code online, you can read the file on GitHub. This will be the last Advent of Code article for a little while, though I'll be continuing with video walkthrough catch-up on Thursdays. I'm sure I'll come back to it before too long, since there's a lot of depth to explore, especially with the harder problems.

If you're enjoying this content, make sure to subscribe to Monday Morning Haskell! If you sign up for our mailing list, you'll get our monthly newsletter, as well as access to our Subscriber Resources!

Advent of Code: Days 19 & 20 Videos

You can now find two more Advent of Code videos on our YouTube channel! You can see a summary of all my work on the Advent of Code summary page!

Here is the video for Day 19, another difficult graph problem involving efficient use of resources! (The write-up can be found here).

And here's the Day 20 video, a tricky problem involving iterated sequences of numbers. You can also read about the problem in our writeup.

Reflections on Advent of Code 2022

Now that I've had a couple weeks off from Advent of Code, I wanted to reflect a bit on some of the lessons I learned after my second year of doing all the puzzles. In this article I'll list some of the things that worked really well for me in my preparation so that I could solve a lot of the problems quickly! Hopefully you can learn from these ideas if you're still new to using Haskell for problem solving.

Things that Worked

File Template and Tests

In 2021, my code got very disorganized because I kept reusing the same module, but eventually needed to pick an arbitrary point to start writing a new module. So this year I prepared my project by having a Template File with a lot of boilerplate already in place. Then I prepared separate modules for each day, as well as a test-harness to run the code. This simplified the process so that I could start each problem by just copying and pasting the inputs into pre-existing files and then run the code by running the test command. This helped me get started a lot faster each day.

Megaparsec

It took me a while to get fluent with the Megaparsec library. But once I got used to it, it turned out to be a substantial improvement over the previous year when I did most of the parsing by hand. Some of my favorite perks of using this library included easy handling of alternatives and recursive parsing. I highly recommend it.

Utilities

Throughout this year's contest, I relied a lot on a Utilities file that I wrote based on my experience from 2021. This included refactored code from that year for a lot of common use cases like 2D grid algorithms. It especially included some parsing functions for common cases like numbers and grids. Having these kinds of functions at my disposal meant I could focus a lot more on core algorithms instead of details.

List Library Functions

This year solidified my belief that the Data.List library is one of the most important tools for basic problem solving in Haskell. For many problems, the simplest solution for a certain part of the problem often involved chaining together a bunch of list functions, whether from that library or just list-related functions in Prelude. For just a couple examples, see my code for Day 1 and Day 11

Earlier in 2022 I did several articles on List functions and this was very useful practice for me. Still, there were times when I needed to consult the documentation, so I need more practice to get more fluent! It's best if you can recall these functions from memory so you can apply them quickly!

Data Structures

My series on Data Structures was also great practice. While I rarely had trouble selecting the right data structure back in 2021, I felt a lot more fluent this year applying data structure functions without needing to consult documentation. So I highly recommend reading my series and getting used to Haskell's data structure APIs! In particular, learning how to fold with your data structures will make your code a lot smoother.

Folds and For Loops

Speaking of folds, it's extremely important to become fluent with different ways of using folds in your solutions. In most languages, for-loops will be involved in a lot of complex tasks, and in Haskell folds are the most common replacement for for-loops. So get used to using them, including in a nested fashion!

In fact, the pattern of "loop through each line of input" is so common in Advent of Code that I had some lines in my file template for this solution pattern! (Incidentally, I also had a second solution pattern for "state evolution" which was also useful).

Graph Algorithms

Advent of Code always seems to have graph problems. The Algorithm.Search library helps make these a lot easier to work through. Learn how to use it! I first stumbled it on it while writing about Dijkstra's Algorithm last year.

The Logger Monad

I wrote last year about wanting to use the Logger monad to make it easier to debug my code. This led to almost all of my AoC code this year using it, even when it wasn't necessary. Overall, I think this was worth it! I was able to debug problem much faster this year when I ran into issues. I didn't get stuck needing to go back and add monads into pure code or trying to use the trace library.

Things I Missed

There were still some bumps in the road though! Here are a couple areas where I needed improvement.

Blank Lines in Input

Certain problems, like Day 1, Day 11, Day 13 and Day 19, incorporated blank lines in the input to delineate between different sections.

For whatever reason, it seems like 2021 didn't have this pattern, so I didn't have a utility for dealing with this pattern and spent an inordinate amount of time dealing with it, even though it's not actually too challenging.

Pruning Graph Algorithms

Probably the more important miss in my preparation was how I handled the graph problems. In last year's edition, there were only a couple graph problems, and I was able to get answers reasonably quickly simply by applying Dijkstra's algorithm.

This year, there were three problems (Day 16, Day 19 & Day 24) that relied heavily on graph algorithms. The first two of these were generally considered among the hardest problems this year.

For both of these, it was easy enough to frame them as graph problems and apply an algorithm like Dijkstra's or BFS. However, the scale of the problem proved to be too large to finish in a reasonable amount of time with these algorithms.

The key in all three problems was to apply pruning to the search. That is, you needed to be proactive in limiting the search space to avoid spending a lot of time on search states that can't produce the optimal answer.

Haskell's Algorithm.Search library I mentioned earlier actually provides a great tool for this! The pruning and pruningM functions allow you to modify your normal search function with an additional predicate to avoid unnecessary states.

I also learned more about the A-Star algorithm than I had known before. Previously, I'd vaguely thought of A-Star as "Dijkstra with a heuristic", which is kind of correct but not helpful in describing what the heuristic actually does.

I eventually came to the understanding that Dijkstra is comparable to Breadth-First-Search for a weighted graph. A-Star is closer to a Depth-First-Search on a weighted graph. While a normal DFS blindly goes down a path until it finds an end-state, A-Star uses the heuristic to attempt to make sure the first parts of the graph that we search are the most likely to lead us to the goal.

It was difficult to find a heuristic for Days 16 & 19, but I was able to apply A-Star on Day 24 to get a noticeable speed-up.

Conclusion

For the next few Thursdays I'm still going to be catching up on the video walkthroughs from Advent of Code. And then next Monday I'll have one more AoC-related article exploring how we can build an API to access our question inputs without even using the web browser!

Make sure to subscribe to our mailing list if you haven't already to get access to our Subscriber Resources!

Advent of Code: Days 17 & 18 Videos

You can now take a look at my latest videos recapping Advent of Code from last year! If you missed any of the write-ups or videos, you can head to the summary page!

Here’s the Day 17 video, another challenging problem where we had to essentially write a tetris simulator!

And here’s the Day 18 video. This one was much easier than days 16 & 17. The key component here was performing a breadth-first-search in 3D. Here’s the writeup if you missed it.

Writing Haskell with Chat GPT

In our last couple of articles, we've asked Chat GPT a bunch of questions about Haskell and functional programming. Today we're going to do one more exploration to see what kinds of Haskell code this chatbot can write.

Hello World

We'll start with a simple "Hello World" program.

How do I write a "Hello World" program in Haskell?

Chat GPT:

To write a "Hello World" program in Haskell, you can use the putStrLn function from the Prelude, which is Haskell's default library. This function takes a string as an argument and prints it to the console. Here's an example of a simple "Hello World" program in Haskell:

main :: IO ()

main = putStrLn "Hello, World!"This program defines a function main that has the type IO (). The IO type is used for actions that perform input/output, and the () type represents the empty tuple, which has no contents. The main function is special in Haskell because it is the entry point of every executable Haskell program. When the program is run, the main function will be called and the string "Hello, World!" will be printed to the console.

You can compile and run this program using the ghc compiler, which is included with the Haskell Platform. First, save the program to a file named HelloWorld.hs. Then, open a terminal and navigate to the directory where you saved the file. To compile the program, type the following command:

ghc HelloWorld.hsThis will produce an executable file named HelloWorld. To run the program, type the following command:

./HelloWorldThis will print "Hello, World!" to the console.

Commentary

This not only gives the code to run the program, it also gives detailed instructions for running it using GHC. Recommending Stack and GHCup would be better advice for beginners though. I'm sure it would know how to describe using these tools if asked about them. But it would be best if it knew to recommend these tools to someone who didn't know about them. Still, I'm nit-picking a bit here.

Sorting Algorithms

So a "Hello World" program is one of the simplest things you can do though. How does ChatGPT do with writing some algorithmic code? Let's start with a couple simple sorting algorithms, quicksort and mergesort.

How can I write quicksort in Haskell?

Chat GPT:

Here is an implementation of quicksort in Haskell:

quicksort :: Ord a => [a] -> [a]

quicksort [] = []

quicksort (x:xs) = quicksort [y | y <- xs, y <= x] ++ [x] ++ quicksort [y | y <- xs, y > x]This function defines a quicksort that sorts a list of elements that are part of the Ord type class (which includes types like Int, Char, and Double). The function uses a recursive approach to sort the list.

The base case of the recursion is the empty list, which is already sorted. For the recursive case, the function divides the list into three parts:

- A sublist of elements that are less than or equal to the pivot element (x)

- The pivot element itself

- A sublist of elements that are greater than the pivot element

The function then recursively sorts the first and third sublists, and concatenates the sorted sublists with the pivot element to produce the final sorted list.

You can test this implementation by calling quicksort with a list of elements:

quicksort [4, 6, 9, 8, 3, 5, 1, 7, 2]This should return the sorted list [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

How can I write mergesort in Haskell?

Chat GPT:

Here is an implementation of mergesort in Haskell:

merge :: Ord a => [a] -> [a] -> [a]

merge xs [] = xs

merge [] ys = ys

merge (x:xs) (y:ys)

| x <= y = x : merge xs (y:ys)

| otherwise = y : merge (x:xs) ys

mergesort :: Ord a => [a] -> [a]

mergesort [] = []

mergesort [x] = [x]

mergesort xs = merge (mergesort left) (mergesort right)

where

mid = length xs `div` 2

left = take mid xs

right = drop mid xsThis implementation defines a merge function that merges two sorted lists into a single sorted list, and a mergesort function that sorts a list using the merge sort algorithm.

The merge function works by comparing the head elements of the two input lists, and adding the smaller of the two to the result list. It repeats this process until one of the input lists is empty, at which point it appends the remaining elements of the other list to the result.

The mergesort function works by dividing the input list into two halves, sorting each half using a recursive call to mergesort, and then merging the two sorted halves using the merge function.

You can test this implementation by calling mergesort with a list of elements:

mergesort [4, 6, 9, 8, 3, 5, 1, 7, 2]This should return the sorted list [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

Commentary

For quicksort, it comes up with a simple 3-line solution, and the mergesort solution is also quite succinct. However, one change I would make to the solution is to tail recursion. As with the "Hello, World" example though, the descriptions are very helpful for someone just learning the language.

Heap Sort

Quicksort and mergesort are one thing. These algorithms have fairly straightforward recursive implementations that work well in Haskell. What about heapsort?

How can I write heapsort in Haskell?

Chat GPT:

Here is an implementation of heapsort in Haskell:

heapify :: Ord a => [a] -> [a]

heapify xs = heapify' (length xs `div` 2 - 1) xs

where

heapify' (-1) xs = xs

heapify' i xs = heapify' (i - 1) (heapifyOne i xs)

heapifyOne :: Ord a => Int -> [a] -> [a]

heapifyOne i xs = case cmp of

GT -> xs

_ -> heapifyOne' i cmp xs

where

cmp = compare (xs !! i) (xs !! child)

child = if r < length xs && xs !! r > xs !! l then r else l

l = 2 * i + 1

r = 2 * i + 2

heapifyOne' i GT xs = xs

heapifyOne' i _ xs = heapifyOne (if r < length xs && xs !! r > xs !! l then r else l) $ swap i (if r < length xs && xs !! r > xs !! l then r else l) xs

where

l = 2 * i + 1

r = 2 * i + 2

swap i j xs = [if k == i then xs !! j else if k == j then xs !! i else xs !! k | k <- [0..length xs - 1]]

sort :: Ord a => [a] -> [a]

sort [] = []

sort xs = y : sort ys

where

(y:ys) = heapify xsThis implementation defines a heapify function that turns a list into a heap, and a sort function that sorts a list using the heap sort algorithm.

The heapify function works by recursively transforming the list into a heap, starting from the middle of the list and working towards the beginning. It does this by repeatedly calling the heapifyOne function, which restores the heap property to a single element and its children in the heap.

The sort function works by repeatedly extracting the maximum element (the root of the heap) and placing it at the end of the result list, until the heap is empty.

You can test this implementation by calling sort with a list of elements:

sort [4, 6, 9, 8, 3, 5, 1, 7, 2]This should return the sorted list [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

Commentary

Very impressive, especially with the detailed description! This time, we do see tail recursion applied in the heapify function.

List Functions

How does it do with a more abstract prompt? I came up with this question based on Day 1 of the recently concluded 2022 Advent of Code.

Write a Haskell function to solve the following problem. The input is a list of lists of integers. We want to find the three lists with the largest sums, and add their sums together. So the output is just an integer.

Chat GPT:

Here is a function that solves the problem you described:

largestThreeSums :: [[Int]] -> Int

largestThreeSums xs = sum $ take 3 $ sortBy (flip compare) $ map sum xsThis function first applies the sum function to each sublist in xs, producing a list of sums. It then sorts this list in descending order using the sortBy function, and takes the first three elements using the take function. Finally, it sums these three elements using the sum function and returns the result.

To use this function, you can call it with a list of lists of integers as an argument:

largestThreeSums [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9], [10, 11, 12]]This should return the result 33, which is the sum of the three largest sublists [7, 8, 9], [10, 11, 12], and [4, 5, 6].

Commentary

This is quite similar to my solution! So Chat GPT did an effective job parsing my description, and determining the right list functions to use to make an efficient, one-line solution.

Making a Server

For one more example, let's try doing something more practical, like a web server. This will require using libraries beyond Haskell's base packages. Once again, this works quite well!

How can I write a basic HTTP server in Haskell?

Chat GPT:

Here is an example of a basic HTTP server in Haskell using the wai and wai-extra libraries:

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

import Network.Wai

import Network.Wai.Handler.Warp

import Network.HTTP.Types (status200)

import Blaze.ByteString.Builder (copyByteString)

import qualified Data.ByteString.UTF8 as BU

app :: Application

app request respond = respond $

case rawPathInfo request of

"/hello" -> hello

_ -> notFound

where

hello = responseBuilder

status200

[("Content-Type", "text/plain")]

(copyByteString "Hello, World!")

notFound = responseBuilder

status404

[("Content-Type", "text/plain")]

(copyByteString "Not Found")

main :: IO ()

main = do

putStrLn "Listening on port 3000"

run 3000 appThis server listens for incoming HTTP requests on port 3000, and responds with a "Hello, World!" message for requests to the /hello path, and a "Not Found" message for all other paths.

To run this server, save the code to a file and compile it using the ghc compiler:

ghc Server.hsThis will produce an executable file named Server. To start the server, run the executable:

./ServerYou should see the message "Listening on port 3000" printed to the console. You can then send HTTP requests to the server using a tool like curl or by opening a web browser and going to http://localhost:3000/hello. You should receive a "Hello, World!" response for the /hello path, and a "Not Found" response for all other paths.

Conclusion

So overall, Chat GPT does quite well with these basic challenges! It would be interesting to take this further still and see if we could make our server program more and more complex, like adding custom functionality for different routes. But Chat GPT definitely seems useful enough to help with basic tasks, even in a less well-known language like Haskell!

As a final note, I did check (out of curiosity) to see if Chat GPT seemed to know much about this blog. The answer appeared to be a resounding "no", leading to a good laugh for me! I asked, "do you know about Monday Morning Haskell?" This was the response I got from Chat GPT (emphasis is mine):

Yes, I am familiar with the term "Monday Morning Haskell." It refers to a programming style or approach that involves using the Haskell programming language to solve problems or write software on a Monday morning, with the implication being that Haskell is a particularly well-suited language for starting the work week off with a clear and focused mind. Haskell is a functional programming language known for its strong static type system, expressive type inference, and purity (lack of side effects). Many developers find that programming in Haskell can help them write clearer, more concise, and more maintainable code, and that it is especially well-suited for tasks that require reasoning about abstract concepts or dealing with complex data.

I might just have to add that description to the home page!

Advent of Code Video Catchup Begins!

If you were following my Advent of Code series from December, you may have noticed that I stopped publishing videos after Day 14 or so. Unfortunately, the problems got challenging, so I didn't have time for videos in addition to writeups. I also went on vacation for Christmas, so I was away from my recording setup for a while.

But now I'm hoping to catch up with those videos! I'll be releasing two each week on Wednesday and Thursday. So today, you can now go to my YouTube channel and see the videos for Day 15 and Day 16!

If you enjoy the Advent of Code series and all the writeups I did, make sure to subscribe to our monthly newsletter!

Day 15

Day 16

Note, the Day 16 writeup is combined with Day 17 and gives only a high-level overview.

Chat GPT and Functional Programming

Last week I explored what Chat GPT has to say about monads. But it's interesting to go beyond this single area and see what its thoughts are about functional programming (FP) in general, and how different languages fit within this paradigm.

So I asked the bot a few questions in these areas to see its response. In each section, the question is either the header, or if it is a longer question, it is given as a quote below the header. This will then be followed by Chat GPT's answer. I'll then follow most sections with some commentary.

We'll see that despite providing a lot of useful knowledge, the bot still sometimes struggles with consistency and the handling of ambiguous and contentious issues.

What is Functional Programming?

Chat GPT:

Functional programming is a programming paradigm that treats computation as the evaluation of mathematical functions. It is based on the idea of immutability and the avoidance of changing state and mutable data. In functional programming, functions are first-class citizens, meaning that they can be passed as arguments to other functions and returned as values from functions. This allows for the creation of higher-order functions that take other functions as input or return them as output.

Functional programming languages typically provide features such as higher-order functions, anonymous functions, and lazy evaluation to support the functional programming paradigm. Some examples of functional programming languages include Lisp, ML, Haskell, and Erlang.

Functional programming has a number of advantages, including the ability to write code that is easier to reason about, easier to test, and less prone to errors. It can also be more efficient in some cases, since it avoids the overhead of mutable state and allows for the use of techniques such as memoization and parallelization. However, it can also be more difficult to understand and learn for programmers who are used to imperative programming styles.

Commentary

So we start with an abstract definition: FP is a paradigm that views programming as the evaluation of mathematical functions. Then we get a slew of features (immutable state, functions as first class citizens, etc.). The features it lists include lazy evaluation, which is noteworthy.

It's interesting though to compare the advantages and disadvantages the bot mentions. It says that functional code is "easier" to reason about and test. It also lists efficiency as an important feature.

It then claims a disadvantage is that it is more difficult to understand...but mainly for people coming from imperative styles. So overall it should be easier to understand, but programmers who have been trained in other systems have a difficult time migrating to FP.

We'll come back to a number of these points later. But first, let's ask about a couple other languages and how they relate to functional programming.

Is C++ a Functional Language?

Chat GPT:

C++ is a multi-paradigm programming language, meaning that it supports several programming paradigms, including functional programming. However, C++ is not a purely functional language, as it also supports other paradigms such as imperative programming and object-oriented programming.

While C++ does not have some of the features that are commonly found in functional programming languages, such as first-class functions and lazy evaluation, it does support the creation of functions and the use of function pointers, which allows for the use of functional programming techniques to some extent.

For example, it is possible to write code in C++ that uses higher-order functions, anonymous functions, and recursive functions, which are all common features of functional programming languages. However, C++ does not have some of the other features that are commonly found in functional programming languages, such as pattern matching and algebraic data types.

Is Rust a Functional Language?

Chat GPT:

Like C++, Rust is a multi-paradigm programming language that supports functional programming, among other paradigms. Rust provides a number of features that make it suitable for functional programming, such as first-class functions, pattern matching, and algebraic data types.

However, Rust is not a purely functional language, as it also supports imperative programming and object-oriented programming. Rust's support for functional programming is more limited than that of languages that were specifically designed for functional programming, such as Haskell or ML.

Despite this, Rust's support for functional programming is sufficient to allow developers to write code in a functional style, and many Rust developers use functional programming techniques in their Rust code.

Commentary

What we see here is the difference between "what is functional programming" and "what is a functional language". C++ and Rust both allow you to use functional programming techniques even if FP isn't their primary paradigm. They're both intended to be flexible, multi-paradigm languages.

However, Rust facilitates FP much more through specific features, specifically abstract data types and pattern matching. Features like these are definitely an important part of why, culturally speaking, Rust programmers are more likely to employ functional programming ideas in their code.

What about the reverse? Does Chat GPT think we can use Haskell for Object Oriented Programming (OOP)?

Can Haskell be used in an object-oriented way?

Chat GPT:

Haskell is a purely functional programming language, which means that it does not support object-oriented programming as a primary paradigm. However, that does not necessarily mean that it is impossible to write object-oriented code in Haskell.

One way to write object-oriented code in Haskell is to use a typeclass-based approach, where types are defined as data types and behaviors are defined as functions on those data types. This can provide a way to define classes and objects, and to define methods on those objects.

Another way to write object-oriented code in Haskell is to use the "Object I/O" library, which provides a set of libraries and tools for building graphical user interface (GUI) applications in Haskell using an object-oriented style. This library allows developers to define classes, objects, and methods in a way that is similar to object-oriented languages such as Java or C++.

Overall, while Haskell is not a language that was designed for object-oriented programming, it is possible to use it in an object-oriented way with some effort. However, the functional programming paradigm is more idiomatic in Haskell, and most Haskell code is written in a functional style.

Commentary

This answer arrives at a conclusion I've had for a while. Typeclasses provide most of the abstraction you really need to get a lot of the benefits of OOP. Of course, they don't inherently provide stateful mutations, which are implicit in OOP, but this is possible to include in Haskell with the State monad.

It is interesting to see the trend that FP is a "more restrictive" paradigm. FP languages don't naturally address OOP as easily or as often as OOP languages allow functional ideas. But I would spin this as a positive for FP. Java and C++ have added more functional features (especially with lambda syntax) in the last few years because functional ideas are inherently useful. Haskell doesn't feel the need to incorporate OOP ideas as much because it doesn't need them.

Lazy Evaluation

In response to the first question, the bot included "lazy evaluation" as one of the features of functional programming, even though this is more specific to a few languages than to the whole paradigm. So I asked the following question:

Is lazy evaluation a defining characteristic of functional programming? Are there functional languages that use eager evaluation?

Chat GPT:

Lazy evaluation is a common feature of functional programming languages, but it is not a defining characteristic of functional programming. Lazy evaluation is a evaluation strategy that delays the evaluation of an expression until it is needed, rather than evaluating it as soon as it is bound to a variable.

Lazy evaluation can be useful in functional programming because it allows for the creation of infinite data structures, and it can also lead to more efficient code in some cases by avoiding the computation of unnecessary expressions. However, lazy evaluation is not a requirement for a language to be considered functional.

There are indeed functional programming languages that use eager evaluation, which is the opposite of lazy evaluation. Eager evaluation evaluates expressions as soon as they are bound to a variable, rather than delaying their evaluation until they are needed.

Some examples of functional programming languages that use eager evaluation include Miranda and Mercury. These languages provide many of the same features as lazy functional languages, such as higher-order functions and immutable data structures, but they use eager evaluation instead of lazy evaluation.

Commentary

So it seems like I've caught the bot in a bit of inconsistency. Lazy evaluation is not actually a necessary part of FP (like it implied in its first answer). But it's certainly more common in FP-oriented languages.

Disadvantages of FP

You said functional programming is more difficult to understand for programmers used to an imperative style. Are there any other disadvantages to functional programming?

Chat GPT:

Functional programming can be more difficult to understand for programmers who are used to imperative programming styles because it involves a different way of thinking about computation. In functional programming, the emphasis is on expressing the desired result of a computation rather than specifying how the computation should be performed, which can be a shift for programmers who are used to an imperative approach.

There are a few other potential disadvantages to functional programming to consider:

- Performance: In some cases, functional code can be less efficient than imperative code, particularly if it makes heavy use of higher-order functions or lazy evaluation.

- Debugging: Debugging functional code can be more difficult in some cases because it can be harder to understand the flow of control in a functional program, especially if the program makes heavy use of higher-order functions or anonymous functions.

- Lack of familiar libraries: Depending on the language, the functional programming ecosystem may not have as many libraries and frameworks available as other paradigms. This can make it more difficult to build certain types of applications, and may require more work to integrate functional code with existing systems.

- Limited adoption: Functional programming is not as widely used as imperative programming, which means that there may be a smaller pool of developers with functional programming experience to draw from. This can make it more difficult to find developers with functional programming skills, and can also make it more difficult to find resources and documentation when learning functional programming.

It's worth noting that these disadvantages are not unique to functional programming, and many of them can be mitigated with the right tools and techniques. Ultimately, the choice of programming paradigm should be based on the needs of the project and the preferences of the development team.

Commentary

So two of the 4 disadvantages still mainly come down to "Haskell/FP are hard because fewer people use them". If there was wider adoption (point #4), then there would be more familiar libraries (point #3).

It's curious though that performance is now listed as a disadvantage when "efficiency" was given as an advantage before! But both points are salient. Immutability does make parallelization easier, but a variety of issues can make FP less efficient, especially in Haskell, where a simple action like changing a value in a contiguous array might require re-copying the whole array.

Debugging is definitely an important issue to list as a disadvantage. Besides GHCI, I haven't used a specific debugging tool for Haskell with much success, so this is a good topic to explore.

In this discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of FP, I thought it would be a good idea to check on formal research in the area. Here's what Chat GPT had to say:

Research

You said functional programming can be easier to reason about and easier to test. Are there experiments or research comparing functional programming and other paradigms in these areas?

Chat GPT:

There have been a number of studies and surveys conducted over the years that have compared functional programming with other paradigms in terms of readability, maintainability, and other factors. These studies have generally found that functional programming can be easier to reason about and easier to test in some cases, although the results are not always clear-cut and can depend on a variety of factors.

For example, a study published in the Journal of Systems and Software in 2002 compared the maintainability of functional, imperative, and object-oriented programs and found that functional programs had fewer maintenance-related defects and were easier to understand than imperative programs.

Another study published in the Journal of Functional Programming in 2005 surveyed developers who had used both functional and imperative programming languages and found that the functional programmers reported fewer debugging and testing problems, and felt that their programs were easier to understand and modify.

Overall, it seems that functional programming can offer some benefits in terms of readability and testability, but more research is needed to determine the extent to which these benefits hold up in practice. It's also important to note that the choice of programming paradigm is just one factor that can impact the readability and maintainability of code, and other factors such as code style, architecture, and the use of good design practices can also be important.

Are There More Recent Studies?

Chat GPT:

There have been a number of more recent studies and surveys that have compared functional programming with other paradigms in terms of readability, maintainability, and other factors.

For example, a study published in the Journal of Systems and Software in 2015 examined the effect of functional programming on the reliability of software systems and found that functional programs had fewer defects and were easier to understand than imperative programs.

Another survey published in the ACM SIGPLAN Haskell Symposium in 2018 surveyed developers who had used both functional and imperative programming languages and found that the functional programmers reported fewer debugging problems and felt that their programs were easier to understand and modify.

Overall, it seems that the results of these more recent studies are consistent with the findings of earlier studies, which is that functional programming can offer some benefits in terms of readability, maintainability, and reliability, but more research is needed to determine the extent to which these benefits hold up in practice.

Linking to Studies

Can you link me to these studies?

Chat GPT:

Sure! Here are the links to the studies I mentioned:

- "A comparison of the maintainability of object-oriented, imperative and functional programs" (2002): https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0164121201001866

- "Functional programming experience: A survey of functional and imperative programmers" (2005): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220654465_Functional_programming_experience_A_survey_of_functional_and_imperative_programmers

- "Functional programming and the reliability of software systems" (2015): https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0164121214001442

- "The State of Haskell in Industry" (2018): https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3236779.3236782

Commentary

Similar to my experience with asking Chat GPT for monad tutorials, none of these links work unfortunately. So Google is still definitely a better option for finding research and tutorials. But the summary we get from the bot is consistent with what I had thought before. A few groups have tried to study FP vs. OOP, and cautiously concluded some small advantages with FP, but it's difficult to resolve this issue conclusively.

Conclusion

Chat GPT provides a very good summary of the broad points about programming issues. However, when you really dig into the details, things aren't always completely consistent, and it is definitely not the best tool for finding research results just yet.

Next week, we'll take one final run with Chat GPT and see if it can write some Haskell code for us!

Monads According to a Robot

To start the new year, I thought it would be fun to spend some time messing around with the item that's all the rage right now - Chat GPT, the newest chatbot published by Open AI.

This chatbot can provide decent answers to most questions you throw at it, similar in concept to Google. However, instead of simply linking to other pages, it can provide fairly detailed and lengthy responses to the question, which Google cannot do. It also does a good job of maintaining conversational context, which is well beyond Google's abilities right now.

So I thought it would be interesting to ask it about a few Haskell-related topics. This week, we'll start with Monads, one of the trickier subjects involved with learning Haskell. I wanted to see how its suggestions line up with my Monads Series.

So the next three sections consist of me asking a question to Chat GPT, and its (often lengthy) response.

What is a Monad?

A monad is a concept from functional programming, which involves structuring programs as a series of computations that are strung together and can be combined in various ways. It's a way of abstracting out certain patterns of computation and making it easier to reuse and compose code. Monads are a bit of an advanced topic, and can be difficult to understand at first, but they can be very powerful once you get the hang of them.

What are Monads used for?

Monads are a powerful concept from functional programming that can be used to structure programs in a way that makes them easier to write, understand, and maintain.

At their core, monads are a way of abstracting out common patterns of computation and making them more modular and reusable. This allows you to write code that is more flexible and easier to work with, and can help you avoid common pitfalls and mistakes.

One of the key benefits of using monads is that they allow you to write code that is more declarative and abstract, rather than focusing on the details of how the computation is actually performed. This can make your code more concise and easier to read, and can help you avoid getting bogged down in the specifics of how the code works.

Another advantage of monads is that they make it easier to combine and compose different pieces of code, allowing you to build larger, more complex programs from smaller, more modular components. This can help you write more flexible and reusable code, and can make it easier to write programs that are modular, maintainable, and easy to understand.

Overall, monads are a powerful tool that can help you write better, more elegant code. They may take some time to understand and get used to, but once you get the hang of them, they can be a valuable asset in your programming toolkit.

How do I use Monads in Haskell?

To use monads in Haskell, you first need to have a basic understanding of the Haskell programming language and how it works. Once you have a handle on the basics, you can start learning about monads and how to use them in your programs.

One way to get started with monads in Haskell is to read through some tutorials or blog posts that introduce the concept and provide examples of how to use monads in your code. There are many resources available online that can help you learn about monads and how to use them in Haskell, including tutorials, blog posts, and videos.

Another way to learn about monads is to experiment with using them in your own programs. This can be a great way to get a feel for how monads work and how they can help you write better code. You can try writing simple programs that use monads, and see how they help you structure your code in a more modular and reusable way.

Overall, the best way to learn how to use monads in Haskell is to dive in and start experimenting with them in your own code. The more you use monads and see how they work, the better you will understand them and be able to apply them in your programs.

My Thoughts

I often describe a monad as a "computational context", and this idea is clearly seen in the bot's response. It talks about "abstracting patterns of computation", which is more or less the same thing. Its response also emphasizes some elements that get lost when we get too far into the weeds of a tutorial, like the modularity and reusability of code. Perhaps I'll go back and re-emphasize those pieces in my own tutorials.

The general response for "how do I use monads" is also good. Reading tutorials helps, and writing your own programs is ultimately essential. I'll link once again to my tutorial series, which contains some code examples you can try for yourself. For more detailed examples that allow you to work on your own project code, you can also try out my two monad-related courses, Making Sense of Monads, and Effectful Haskell.

Limitations

Unfortunately, the bot does a surprisingly poor job providing links to such tutorials. It provided me with several examples of blog posts that sounded very convincing, like "All About Monads by Brent Yorgey", and then it would link me to Brent Yorgey's blog page with a URL that contained the title "All About Monads" from 2009 or so. But the link was broken, suggesting the specific post of that title never existed. (Incidentally, the Haskell Wiki contains a page for All About Monads, but it doesn't seem as though Brent Yorgey was a contributor).

This process repeated with 3-4 different suggestions. It would have a monad related title, the name of a notable Haskell practitioner, and a link that seemed link it should work. And yet the link would be broken. In one case, it gave the title of Monads for the Working Haskell Programmer but attributed this work to Bartosz Milewski (instead of Theodore Newell, plainly listed as the author at the top of the page) along with an incorrect link (I found the correct link after googling the title).

I would have expected the bot to check links before supplying them, so this was definitely surprising behavior.

I also tried to push the boundaries and see if it could write a code-based tutorial for me. It would start writing some promising looking code, but eventually the whole thing would get deleted! Perhaps the code was getting too long and I was getting rate limited, I'm not sure. I'll experiment more with having it write code in the coming weeks.

Day 25 - Balanced Quinary

This is it - the last problem! I'll be taking a bit of a break after this, but the blog will be back in January! At some point I'll have some more detailed walkthroughs for Days 16 & 17, and I'll get to video walkthroughs for the second half of problems as well.

Subscribe to Monday Morning Haskell!

Problem Overview

Today's problem only has 1 part. To get the second star for the problem, you need to have gotten all the other stars from prior problems. For the problem, we'll be decoding and encoding balanced quinary numbers. Normal quinary would be like binary except using the digits 0-4 instead of just 0 and 1. But in balanced quinary, we have the digits 0-2 and then we have the - character representing -1 and the = character representing -2. So the number 1= means "1 times 5 to the first power plus (-2) times 5 to the zero power". So the numeral 1= gives us the value 3 (5 - 2).

We'll take a series of numbers written in quinary, convert them to decimal, take their sum, and then convert the result back to quinary.

Parsing the Input

Here's a sample input:

1=-0-2

12111

2=0=

21

2=01

111

20012

112

1=-1=

1-12

12

1=

122Each line has a series of 5 possible characters, so parsing this is pretty easy. We'll convert the characters directly into integers for convenience.

parseInput :: (MonadLogger m) => ParsecT Void Text m InputType

parseInput = sepEndBy1 parseLine eol

type InputType = [LineType]

type LineType = [Int]

parseLine :: (MonadLogger m) => ParsecT Void Text m LineType

parseLine = some parseSnafuNums

parseSnafuNums :: (MonadLogger m) => ParsecT Void Text m Int

parseSnafuNums =

(char '2' >> return 2) <|>

(char '1' >> return 1) <|>

(char '0' >> return 0) <|>

(char '-' >> return (-1)) <|>

(char '=' >> return (-2))Decoding Numbers

Decoding is a simple process.

- Reverse the string and zip the numbers with their indices (starting from 0)

- Add them together with a fold. Each step will raise 5 to the index power and add it to the previous value.

translateSnafuNum :: [Int] -> Integer

translateSnafuNum nums = foldl addSnafu 0 (zip [0,1..] (reverse nums))

where

addSnafu prev (index, num) = fromIntegral (5 ^ index * num) + prevThis lets us "process" the input and return an Integer representing the sum of our inputs.

type EasySolutionType = Integer

processInputEasy :: (MonadLogger m) => InputType -> m EasySolutionType

processInputEasy inputs = do

let decimalNums = map translateSnafuNum inputs

return (sum decimalNums)Encoding

Now we have to re-encode this sum. We'll do this by way of a tail recursive helper function. Well, almost tail recursive. One case technically isn't. But the function takes a few arguments.

- The "remainder" of the number we are trying to encode

- The current "power of 5" that is the next one greater than our remainder number

- The accumulated digits we've placed so far.

So here's our type signature (though I flipped the first two arguments for whatever reason):

decimalToSnafuTail :: (MonadLogger m) => Integer -> Integer -> [Int] -> m [Int]

decimalToSnafuTail power5 remainder accum = ...It took me a while to work out exactly what the cases are here. They're not completely intuitive. But here's my list.

- Base case: absolute value of remainder is less than 3

- Remainder is greater than half of the current power of 5.

- Remainder is at least 2/5 of the power of 5.

- Remainder is at least 1/5 of the power of 5.

- Remainder is smaller than 1/5 of the power of 5.

Most of these cases appear to be easy. In the base case we add the digit itself onto our list and then reverse it. In cases 3-5, we place the digit 2,1 and 0, respectively, and then recurse on the remainder after subtracting the appropriate amount (based on the "next" smaller power of 5).

decimalToSnafuTail :: (MonadLogger m) => Integer -> Integer -> [Int] -> m [Int]

decimalToSnafuTail power5 remainder accum

| abs remainder < 3 = return $ reverse (fromIntegral remainder : accum)

| remainder > (power5 `quot` 2) = ...

| remainder >= 2 * next5 = decimalToSnafuTail next5 (remainder - (2 * next5)) (2 : accum)

| remainder >= power5 `quot` 5 = decimalToSnafuTail next5 (remainder - next5) (1 : accum)

| otherwise = decimalToSnafuTail next5 remainder (0 : accum)

where

next5 = power5 `quot` 5This leaves the case where our value is greater than half of the current power5. This case is the one that introduces negative values into the equation. And in fact, it means we actually have to "carry a one" back into the last accumulated value of the list. We'll have another "1" for the current power of 5, and then the remainder will start with a negative value.

What I realized for this case is that we can do the following:

- Carry the 1 back into our previous accumulation

- Subtract the current remainder from the current power of 5.

- Derive the quinary representation of this value, and then invert it.

Fortunately, the "carry the 1" step can't cascade. If we've placed a 2 from case 3, the following step can't run into case 2. We can think of it this way. Case 3 means our remainder is 40-50% of the current 5 power. Once we subtract the 40%, the remaining 10% cannot be more than half of 20% of the current 5 power. It seems

Now case 2 actually isn't actually tail recursive! We'll make a separate recursive call with the smaller Integer values, but we'll pass an empty accumulator list. Then we'll flip the resulting integers, and add it back into our number. The extra post-processing of the recursive result is what makes it "not tail recursive".

decimalToSnafuTail :: (MonadLogger m) => Integer -> Integer -> [Int] -> m [Int]

decimalToSnafuTail power5 remainder accum

| abs remainder < 3 = return $ reverse (fromIntegral remainder : accum)

{- Case 2 -}

| remainder > (power5 `quot` 2) = do

let add1 = if null accum then [1] else head accum + 1 : tail accum

recursionResult <- decimalToSnafuTail power5 (power5 - remainder) []

return $ reverse add1 ++ map ((-1) *) recursionResult

{- End Case 2 -}

| remainder >= 2 * next5 = decimalToSnafuTail next5 (remainder - (2 * next5)) (2 : accum)

| remainder >= power5 `quot` 5 = decimalToSnafuTail next5 (remainder - next5) (1 : accum)

| otherwise = decimalToSnafuTail next5 remainder (0 : accum)

where

next5 = power5 `quot` 5Once we have this encoding function, tying everything together is easy! We just source the first greater power of 5, and translate each number in the resulting list to a character.

findEasySolution :: (MonadLogger m) => EasySolutionType -> m String

findEasySolution number = do

finalSnafuInts <- decimalToSnafuTail first5Power number []

return (intToSnafuChar <$> finalSnafuInts)

where

first5Power = head [n | n <- map (5^) [0,1..], n >= number]

intToSnafuChar :: Int -> Char

intToSnafuChar 2 = '2'

intToSnafuChar 1 = '1'

intToSnafuChar (-1) = '-'

intToSnafuChar (-2) = '='

intToSnafuChar _ = '0'And our last bit of code to tie these parts together:

solveEasy :: FilePath -> IO String

solveEasy fp = runStdoutLoggingT $ do

input <- parseFile parseInput fp

result <- processInputEasy input

findEasySolution resultAnd that's the solution! All done for this year!

Video

Coming eventually.

Day 24 - Graph Problem Redemption

I don't have enough time for a full write-up at the moment, but I did complete today's problem, so I'll share the key insights and you can take a look at my final code on GitHub. I actually feel very good about this solution since I finally managed to solve one of the challenging graph problems (see Days 16 and 19) without needing help.

My first naive try at the problem was, of course, too slow. but I came up with a couple optimizations I hadn't employed before to bring it to a reasonable speed. I get the final solution in about 2-3 minutes, so some optimization might still be possible, but that's still way better than my 30-40 minute solution on Day 16.

Subscribe to Monday Morning Haskell!

Problem Overview